NatureZen: Happy Bee Day to You

Words and photos by Melissa McMasters

Today is World Bee Day, an international effort to convey the importance of bees to our food systems and to the diversity of life on our planet. One of every three bites of food we eat is dependent on bees, and their numbers are declining worldwide. The plight of the honey bee has gotten most of the publicity–after all, everyone knows what a honey bee is, right? But as usual, the full story is more complicated.

The familiar Western honey bee isn’t native to the United States; it was brought here by European settlers in the 1600s and quickly escaped domestic hives to colonize landscapes across the country. But there are more than 4,000 bee species that are native to the U.S., all of which evolved along with our native plants to create functioning ecosystems. Honey bees wound up being well-suited to industrial agriculture and mass food production, but their rise displaced many native bees. The pollinator crisis was happening before most of us ever heard the term “colony collapse disorder,” the mysterious and sudden loss of entire honey bee hives that began making news just over a decade ago.

Because our native bees aren’t present in nearly the same numbers as honey bees, we may rarely notice them as they do the jobs they were born to do, pollinating our tomatoes, squash, and blueberry plants. But because industrial agriculture dominates so much of America’s land, our parks and yards are actually the perfect places to nourish healthy native bee populations. So before we meet some of these incredible creatures, here are some things you can do for native bees:

- Grow native plants! If you’re a home gardener, mix in native wildflowers like coneflowers and black-eyed susan with your vegetables and herbs. Avoid buying plants treated with pesticides (one way to do this is by planting from seed). The Xerces Society has a list of ideal plants for our region and a guide to buying bee-safe plants.

- Rethink your approach to mosquito control. Spraying chemicals to kill adult mosquitoes should be a last resort, as these treatments harm pollinators and are easily spread by wind. Focus on eliminating opportunities for mosquito larvae to grow. Here’s a great resource on controlling mosquitoes with less collateral damage.

- Learn about all the ways you can make your yard pollinator-friendly.

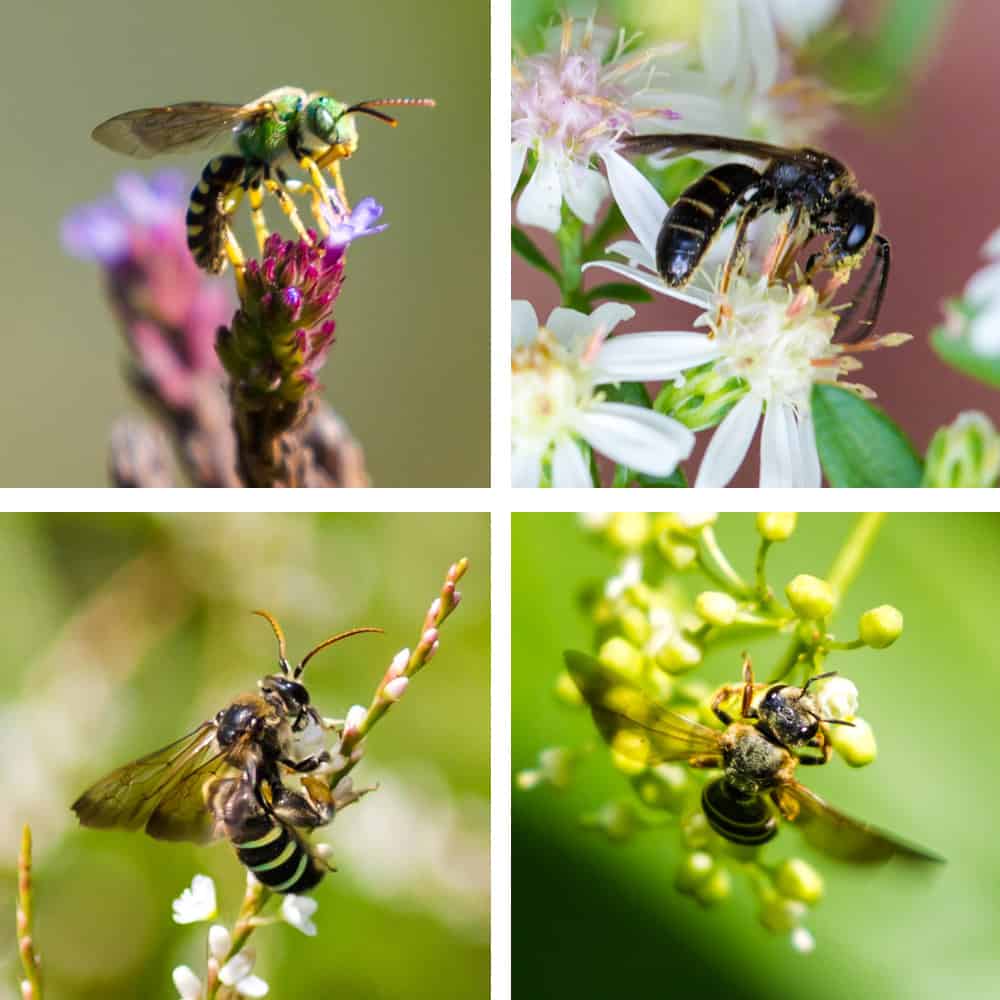

The first step, though, is to start noticing the native bees you encounter! Searching for native bees around Memphis was my pandemic-isolation hobby last year, and it is nearly impossible for me to narrow down the list of these extraordinary creatures to share only a few with you. But here are some of my favorites.

Do I love long-horned bees the best because many of them occupy a genus called Melissodes, or because their extra-long antennae give them such personality? Either way, I’m always thrilled to see them. The males of this group are the ones with the long “horns,” while the females are more distinctive for their big fluffy hind legs, which have extra-long hairs. (These hairs are a pollen-carrying adaptation called the scopa, and they serve the same function as the pollen baskets of a honey bee: storing pollen to carry back to the nest. Some of this pollen, of course, gets transferred to other flowers along the way, allowing plants to reproduce.)

I’ve seldom been more charmed than I was watching this long-horned bee tuck his antennae behind his head and don deadnettle flowers like a wee purple helmet.

The long-horned bees have their pollen-carrying features on their hind legs, but that’s not true of all bees. Leafcutter bees don’t have those long hairs on their hind legs, so the hairs under their bellies form their scopae, as you can see in the top two photos below. Leafcutter bees create nests in long hollow tubes, making small chambers for each egg, lining them with pieces of leaves, and sealing them off with chewed leaves and resin. These bees have extra-large heads because they need the muscles to chew up all those leaves! Leafcutters are great pollinators and not aggressive toward humans, which is why gardeners put up bee hotels for them.

One of the most diverse bee families are the sweat bees, which have a wide variety of both appearances and behaviors. Some species are totally solitary (every female makes and provides for her own nest), while some are more social (several females, often sisters from the same nest, share nest building and rearing young). But why do they drink sweat? It’s because bees need salt to produce eggs, and nectar and pollen don’t provide much of it. We humans eat a lot of salt, so our sweat is a goldmine for these bees!

Cuckoo bees get their name from the birds whose nesting habits they share. These types of bees, along with birds in the cuckoo family, are kleptoparasites, meaning that they steal the nesting cavities of other bees to lay eggs rather than building their own. They can often be found on the ground, staking out the holes of ground-nesting bees in order to sneak inside and lay an egg when the other bee is out foraging for food. Because cuckoo bees aren’t in charge of feeding their young (their nest “victims” take care of that), they lack the features of other bees whose longevity depends on getting lots of pollen to the next generation. In other words, a cuckoo bee has no use for a scopa! These bees are typically less hairy overall, in fact. They still enjoy a good meal of nectar, though!

Those are just a few of the notable types of bees you may find in a walk through the park or in your own backyard, but there are so many more to discover. (I didn’t even mention the bumble bees!) Still want to know more about our incredible native bees? Here’s a great guide.