NatureZen: Aging Like a Fine Vine

words and photos by Melissa McMasters

Within the next week or two, those of you who are on our snail-mail list will receive our summer 2022 newsletter. (You’ll find a PDF here.) Our lead story is a deep dive into every layer of the Old Forest and all the specialized habitat niches found there. That story is meant to provide a holistic picture of how each level of the forest works together, but we could go into much greater detail about each layer. So that’s what we’re doing in today’s NatureZen, where we take a look at a key component of the Old Forest: the vines!

Vines, almost by definition, don’t occupy just one particular layer of the forest. They either sprawl on the ground, or, if they have support, they can reach all the way up to the canopy.

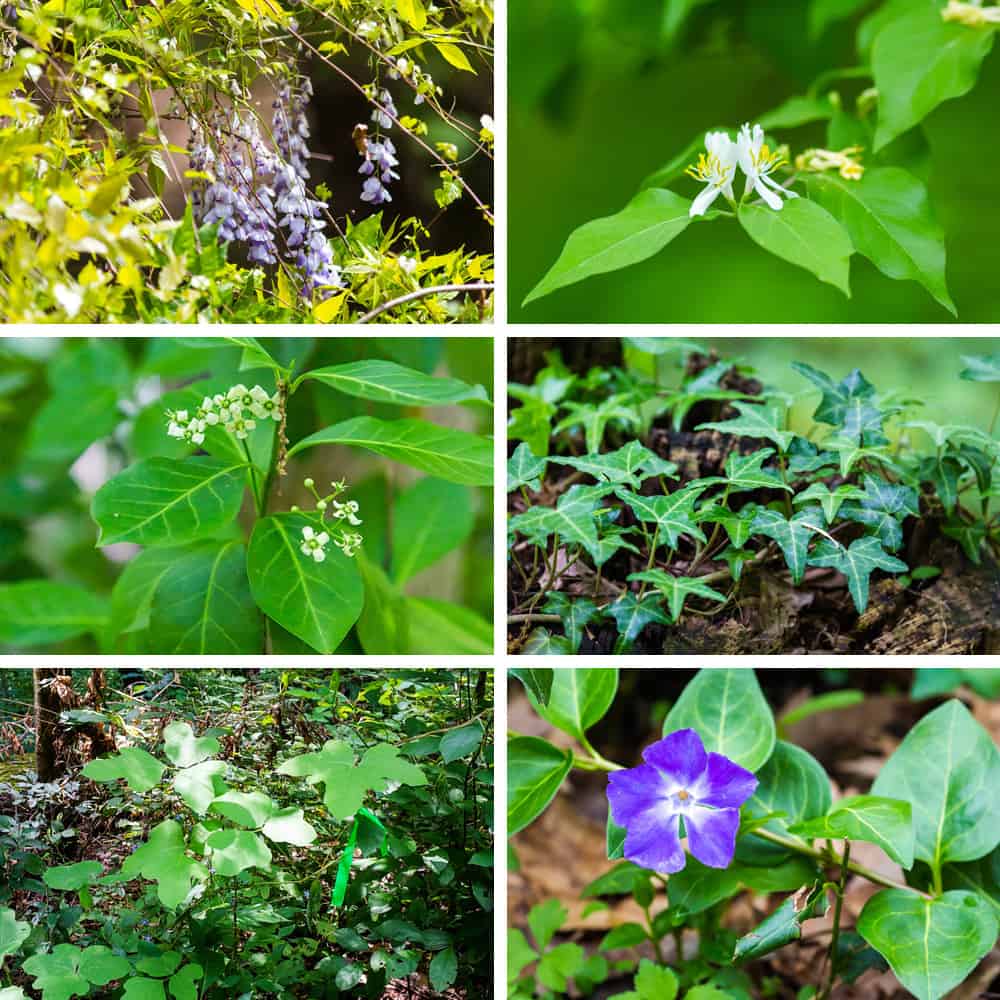

From the leafy Virginia creeper, to the beautiful yellow and red trumpet-like flowers of cross vine, to the decades-old grape vines that are thicker than many surrounding tree trunks, our forest is full of vines — more than three dozen species of them.

If the Old Forest were being managed for timber, vines would be the enemy–they can twist tree trunks as they climb, making the wood less valuable for sale. But because we’re managing for a healthy ecosystem, not for harvesting, we value the habitat niches that the native vines create.

The Old Forest boasts at least five species of native grape vines, including muscadine, called the Grape of the South because it’s particularly happy in places with hot, humid summers. How tall a grape vine gets is often determined by what it’s climbing. In the case of the Old Forest, where we have a good complement of trees over 80 feet tall, they can stretch quite high. The vines grow up along with the trees from their seedling stage, and then sometimes they climb from the canopy of one tree into another. Like these trees, grape vines can live for over a century, although their ability to produce fruit diminishes as time goes on.

Some may look at the above photo and just see a mess, or they may worry about what’s happening to the trees. But vines have an important role to play in the forest just as trees do. In particular, they provide food and shelter to a variety of wildlife.

In the spring, grape vines send out a cluster of flowers that, if pollinated, will turn into grapes. Many grape species can self-pollinate because their flowers are “perfect,” meaning they have both male and female reproductive parts. Others, like muscadine, produce a variety of flowers–some male, some female, some perfect.

No matter what the flower type, though, grape vines produce nectar for pollinators, and they in turn benefit from a bee’s journey from one plant to another. Muscadines have been shown to set significantly more fruit when pollinated by bees.

Muscadines also serve as host plants for several moth species, which means that this is the plant these moths use to lay their eggs. When the caterpillars hatch, they feed on the leaves of the grape vine. Then, these caterpillars either nourish birds or transform into moths that pollinate other plants in the forest. It all works together!

Once the muscadine sets fruit, dozens of species of songbirds and woodpeckers, plus squirrels and raccoons, eat the grapes. Other birds, like robins and red-eyed vireos, use strips of the bark to build their nests.

We’ve focused on grape vines today because they’re one of the signature sights in the forest, one of the many things that make this place special. But there are many other native vines that add color, interest, and habitat value to the forest.

Of course, our forest is also in an urban area, where seeds from vines planted for groundcover, privacy screening, and ornamental value have escaped into a woodland where they have no natural predators. We pursue removal of these invasive vines aggressively, because their ability to both climb and root deeply in the soil makes them very hard to eradicate once they get established.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this look at the role vines play in our forest ecosystem. Check your mailboxes this week to learn how every layer of the forest, from roots to canopy, works in harmony to create a rich mosaic.