Stories: Terry Starr

Terry Starr has a wealth of stories about growing up near Overton Park. Later in her life, the park also brought her some special magic in the form of a treasured friendship. We’re so fortunate that she chose to share those stories with us.

I’m a lifelong Memphian, and I spent the first 20 years of my life living around the corner from Overton Park. When I was in my 50s, I came back to take care of my mother who lived in the same house for 91.5 years. I guess my first memory of Overton Park is of going through the back alley to Kenilworth to the verge of Overton Park to pick crabapples off the ground for crabapple jelly. My mother had told my older brother Paul and me only to pick the crabapples that were on the ground. There weren’t very many, so I being 8 and thinking myself very intelligent, shook the tree so that there would be plenty on the ground. Her crabapple jelly was excellent that year!

I went on weekly trips to the zoo. Each one of us, as we came of age–Dad raised tropical fish and he raised feeder fish for the aquarium at the zoo, which was 25 cents, a mighty big amount of money for a free zoo. Every week Dad would take us to the zoo. I knew the animals by name, I knew the keepers by name. Tommy O’Brien had a free circus at the zoo, and a pony track, and a thrill was that when it was time for me to go to the aquarium, they let me duck under and go in free because Dad supplied guppies for the carnivores to eat.

I remember once going to the zoo and they had a baby elephant with lots and lots of black hair on its head in a separate pen. At noon he would gallop down the main street of the zoo to see his mother. One day I had a bag of popcorn and I offered some to him. He wrapped his trunk around it and took the whole thing, bag and all. I was not happy with him. But I used to pull leaves off the trees and feed them to the giraffes–I don’t think they let you do that anymore.

I used to go to the wading pool and to the summer programs the Park Commission put on. My grandmother was a local LPGA golf champ. We would walk through the neighborhood and the park to gather up sweetgum balls so that she could take them over to the driving range at the park and whack them instead of golf balls that you had to pay for. When I was nine or ten, they had a talent show. I may have been the only entrant, but I remember memorizing “Singing in the Rain” and singing it a capella. I think they gave me the prize because nobody else tried out for anything.

I did remember one summer having to endure sewing school. I still can’t sew. But I had made a gingham dress with bric-a-brac trim, and I leaned too close to Rainbow Lake and fell in. My younger brother used to collect things from Rainbow Lake, and he brought home lots and lots of tadpoles one year. They all turned into little tiny frogs, and he had a box in the middle of his bedroom that somehow got knocked over. All these little dime-sized frogs from Rainbow Lake were everywhere. We went running after them, but found them behind shelves and under radiators weeks later. My mother was ballistic.

I was third-string on every sport that my elementary school provided. There was softball practice, to which I could walk, over near Kenilworth and Overton Park Ave. I remember going to practice softball there, and as an eighth-grader, because I was left-handed, I was the only left-hander in the league. The coach waited until everyone else had hit the ball, because she knew how bad I would be, and she threw the ball, and I whacked it. And she was surprised. She went after it because there was no one else to. She threw it again and I whacked it again. She started showing me how to stand, and then I decided I’m going home. My mom asked how tryouts went and I said, “I quit. I’m never going to get that good again. I better stop while I’m ahead.”

In the spring of 1968, Memphis had one of the biggest snowfalls on record. I had some friends in junior high over on my street who said, “Let’s go sled in the park.” I did the stupidest thing I could think of, just about–we went to the Shell, which was then not in use, and slid down the ramp backstage. That was bad enough, but then they got the idea of sliding down the Art Academy steps, which I did and prayed all the way down. It wasn’t very bumpy, it was a straight shot down because there was so much ice, but it was a dumb thing to do, I will grant that.

Terry and her classmates turned the Old Forest into Sherwood Forest.

I went to Immaculate Conception high school, and during my senior speech class, the teacher got the idea that we should film a silent film. I don’t know what that has to do with speech, but we decided to do “Robin Hood.” When you go to an all-girls school, you have to have some people playing the male parts. I was the Evil Prince John, mainly because we had the red velvet drapes in the living room that were my grandmother’s, and that made a great cape. We filmed near the golf course. I remember that we figured out how to do the archery contest–we would film the archer, and the arrow would already be stuck in the bullseye and we’d zoom in on it. This was in 1970, way before the sophisticated camera work you can do now. We did unfortunately catch one car in Sherwood Forest–we didn’t realize that until we put the film together! But I do remember that we had Maid Marian imprisoned in my castle, which happened to be the Overton Park Golf House, because it had some bars. We had to work up a storyboard, and we wrote that we were going to have a prisoner exchange. Somehow Maid Marian escaped during this, but there’s a shot of my gang–the Sheriff of Nottingham and his boys and myself–marching this veiled prisoner over the golf bridge that the WPA put in back in the 30s. Then there’s Friar Tuck and Little John and everybody. Marian got away, and then they had a shot of me acting out “Curses, foiled again!” or something. I’ll never forget, after it was over, everybody wanted to stop at McDonalds. Only I’m a teenage girl in red tights and a white tunic and a red velvet cape, so I said “Just let me sit in the car.” Friar Tuck didn’t have any such inhibitions–she went barging into McDonalds, but I just couldn’t do it.

Terry’s parents, James and Constance Starr, were on opposite sides of the I-40 controversy in the 1960s and 70s.

Mom and Dad had some altercations, although they never voiced them, about the park because she was one of the kingpins in the Save Our Park campaign. She didn’t want I-40 going through the Old Forest. My father was a draftsman for the company that was intent on putting the expressway through the Old Forest. I remember how complete the silence was. We never, ever talked about it at all.

Her childhood curiosity about art led to one of the most important friendships of her life…and her later encounters with Overton Park.

I spent hours as a youngster at the Brooks Museum. I remember I felt a certain sense of ownership, because at that time both the museum and the zoo were free. So whenever I felt the urge I would go again back down the alley, to Kenilworth, cross over the verge and the bit of lawn, go into the Brooks, and browse. As a child I was fascinated by one particular painting in the Cress collection. It was a painting of the Annunciation. It fascinated me that the angel Gabriel looked as if he had a dislocated big toe, and it also intrigued me that I could see Mary’s braid through the veil. Even as a youngster, I said to myself, “How do they do that?” I couldn’t get enough of it.

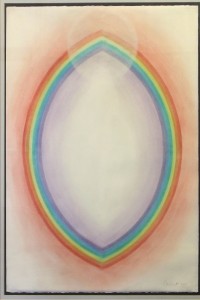

When I got to be a teenager, being a card-carrying introvert, I would go over to the Brooks for solace and quiet. I remember, I think I was probably in college by this time, I saw a wonderful painting called “Homage to the Rainbow #3” by Burton Callicott. I had never heard of him, but again I thought “How does he do that?” Oddly enough, I got to find out how he did it, because years later I was asked by Jim Crosthwaite, who had done a documentary on Burton Callicott that was to be aired during the retrospective in 1991 of Burton’s work, to write a song for the film. He gave me several still shots of Burton’s work, and when I saw the Homage to the Rainbow, I froze the film and said, “This is the same picture that I saw when I was a youngster.” I got to interview Burton in his home, which in the film consisted merely of my saying “ooh” and “ahh” as he took me through an incredible art lesson. I never saw things the same after that. He gave me one of his sketches of a rainbow mandorla as a present for writing the song which was performed at the film. We became friends until the end of his life. I was there the day he died. So in a sense, Brooks Museum and Overton Park brought me my friendship with Burton.

Terry is a music instructor, and her story interweaves with the Shell’s rich musical history.

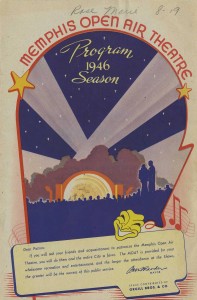

Memphis Open Air Theatre program from the 1940s

My dad was assistant stage manager for the Memphis Open Air Theater for many years. He would often be in the chorus, mainly to direct them in the way that they should go, because he had a lovely light tenor. He said to me for years, “Oh no, I can’t sing.” I asked why he said that. He said because Rudolf Friml’s musical director heard me singing and said, “Jim, are you singing?” He said yes and the musical director said, “Well, don’t.” I said, well, the show is a repertory and you had a week to get it together and he just wanted to get the show going, it wasn’t a comment on your voice. But after that Dad always believed he couldn’t sing. He would take me to the Summer Pops Concerts–they would get in a big star like Anita Bryant. I knew about some of the orchestra members because my great-uncle had played under Noel Gilbert’s baton, who was the conductor for the Summer Pops. Dad would go backstage after the show and talk with the union guys he knew.

I had no idea that I was going to end up performing on the Shell stage twice in my life: once, for the aforementioned documentary, accompanying the Grahamwood Chorus with my piece that I had written for Burton, and once when I was in college. One of our profs had written an oratorio celebrating the history of Memphis. It was a very unique piece. Unfortunately, he got upstaged because it was during the early 70s, during the height of the streaking craze, and an unclad gentleman in tennis shoes went running across the stage during the Mr. Crump section of the oratorio, and got more ink in the paper than Dr. Wade or the piece, which made me mighty mad.

The last time I was in the park aside from this summer’s Day of Merrymaking was the 75th anniversary for the Overton Park Shell. My mother was by this time in her late 90s at Trezevant Manor, and I saw something on the boards saying if anybody had recollections of the Shell, to please call this number because David Wade wanted people to be recorded.

I was going to tell tales about my dad and about going as a kid, and to my great surprise, when I met the filmmaker, he had some programs that he had me look through. Dad used to always want to be behind the scenes–he and Mom met working theater–and Mom always wanted to be in front of the footlights. Unfortunately, Dad would always be called out to do these little bit parts, and Mom (who did not work at the MOAT) was always getting called to be stage manager. Dad used to tell stories about being asked to do the dialect parts. For example, he would say this line, “I am the padrone from the inn!” He didn’t tell me the show or anything. So here, the director hands me a bunch of programs. The name of the program is “Rio Rita,” and the third thing down, there’s my father’s name Jimmy Starr and the character name is Padrone. The thing that was so amazing was that my father was indeed the Padrone from the Inn, my great-uncle Isaac was first viola in the orchestra under Noel Gilbert, and somebody who used to be a dentist on our street was in the chorus. One of Mom’s buddies from the theater was one of the bit parts.

They filmed me looking at the programs and playing some of the pieces that would have been played in the shows. The astounding thing was that they later invited me to this gala and I’m sitting there watching the film. There was an older gentleman in the film who was a lifelong Memphian who was talking about one of the pieces he had sung. By some miracle, it was one of the pieces that I had started to play, called “Stout-Hearted Men,” and by another miracle, we were in the same key and the same tempo. The odds of that are about a million to one. Underneath his film clip, they segued my playing in just like you’d see in a movie. He finished and they played my final chords, and I thought, “Dear God, the miracle of modern cinema.” That was an amazing thing.