NatureZen: Pollinator Paradise

Sometimes small changes can have a big impact, and that’s been made thrillingly clear with Overton Park Conservancy’s addition of two pollinator-friendly planting beds at Veterans Plaza this summer. After we lost the crape myrtles in these raised beds to frost, we took the opportunity to fulfill a long-standing dream: creating a micro-habitat just for pollinators.

With the guidance of Conservancy board member Mary Wilder, and the help of the Evergreen Garden Club and the Daughters of the American Revolution – River City Chapter, in May we installed purple coneflower, bronze fennel, Mexican petunia, parsley, blanket flower, ironweed, and three varieties of native milkweed and waited to see whether the insects would find them. The answer: an emphatic yes. Our Stewardship Manager, Fields Falcone (who has devotedly watered the garden all summer) and our Director of Communications, Melissa McMasters, have documented more than 170 species of insects in just a few square feet over the past three months. We’re so excited to share some of them with you today.

NatureZen: Pollinator Paradise

words and photos by Melissa McMasters

In trying to slow the overwhelming loss of insect populations worldwide, one word reigns supreme: habitat. Insects depend on plants, especially the local native plants they evolved with, for food, shelter, and places to lay their eggs. As more land gets developed, or treated with pesticides, or altered by climate change, insects have fewer places to go. So it’s been a real joy to see how quickly and abundantly the pollinators have rushed into this small space over the last three months.

While we waited to see if the new plantings would take off, we rejoiced at every visitor that came by. Even if there wasn’t much to actually pollinate yet, the insects were interested. Every now and then we’d luck into a sleepy bee resting on the fronds of the fennel plants.

In June we had our first flowers: the Mexican petunias went up like a fountain and have bloomed all summer long. May we all experience a love in our lives like bees have for Mexican petunias. Male hibiscus turret bees (top left below) use the flowers as a vantage point to watch for passing females. Brown-winged striped sweat bees (top right) park themselves inside and take the bee version of a bath, cleaning the pollen from their legs and tongues. Eastern carpenter bees (bottom right) are resourceful enough to grab the last of the nectar even after the flowers have wilted and they can no longer get inside. (This one is piercing the base of the flower with its tongue.) And American bumble bees (bottom left) zoom from flower to flower in rapid succession, loading their pollen baskets up with the orange dust that will fertilize the next flower.

Soon the garden was coming into full bloom, bringing with it a pesky problem. Many of the tender new stems were covered in bright yellow oleander aphids. We wanted to keep this plot pesticide-free, because many of the chemicals that harm pests also cause damage to beneficial insects. So we waited to see whether the aphids would cause serious damage, and were pleased to find that the plants survived and thrived despite them. Plus, the aphids turned out to be a food source for several of our insects, including the four-speckled hover fly. The adults have been laying eggs prolifically on the plants that contain aphids, and the larvae then feed on the pests! The one in the middle photo below is juuuust about ready to start snacking. (Four-speckled hover fly larvae aren’t much to look at.)

There are many types of flies whizzing around the garden, and like the hover fly, they serve different functions depending on their life stage. Larvae are often carnivorous, eating some insects we’re fond of (like bumble bees) and some we’re less thrilled with (like stink bugs). The adults consume nectar and pollen, and the fuzzier they are, the more they spread it around.

We also noted multiple species of lady beetles, which eat aphids as both larvae and adults. While not great pollinators, they play a positive role in the ecosystem by protecting the plants that other insects need. The gardens have plenty of pollinating beetles too, thanks to plants with clusters of small flowers, like lantana and fennel.

One thing the garden has never lacked is a variety of bees. In addition to the Eastern carpenter bee above, there are dozens of small carpenter bees like Ceratina strenua (top left below) present every day. It’s difficult to tell in person that they have bright blue eyes because they’re so tiny! More conspicuous is the carpenter-mimic leafcutter bee, which is also present in good numbers. They may fool you into thinking you’ve seen two different species, because males (top right below) are two-toned and somewhat fuzzy, while females are all-black and smooth. (You can see one in the header image of this email.) It’s hard to know how many kinds of leafcutter bees we have in total, because many of them can’t be identified to species from photos. (What big green eyes you have! I said to this one. Always talk to the bees.) Finally, this Northern rotund-resin bee was small enough to almost fit inside a butterfly milkweed flower, and I only saw it for a few seconds and only on a single day. Some bees are just passing through, while others seem to have recognized a good thing and stuck around.

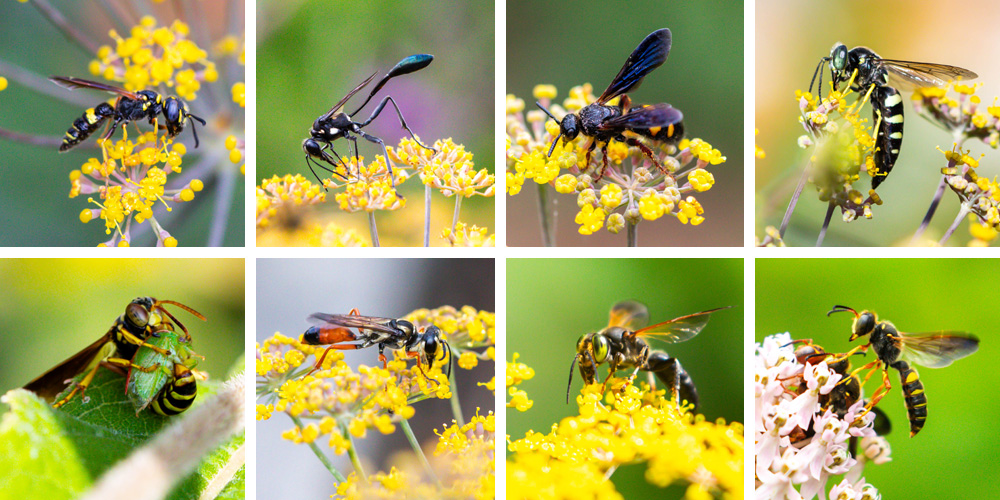

When I suggest to you that you should spend some time hanging out somewhere with a large wasp population, you’re probably going to give me the world’s biggest side-eye. But hear me out: solitary wasps (which comprise the vast majority of wasps you’ll see in the garden) are highly unlikely to sting people, unlike social wasps that nest near homes and guard their dwellings as a group. Female solitary wasps use their stingers to subdue insects that they carry back to their nests in order to feed their young. But most of the time they’re just having a drink. They’re so languid as they bury themselves in fennel blossoms that they might just encourage you to slow down and appreciate the beauty of a much-maligned group of creatures.

Bottom row: Saygorytes phaleratus clutching a three-cornered alfalfa hopper to take back to her nest, Sphex dorsalis, Tachytes guatemalensis, Cerceris bicornuta

Of course, no trip through the pollinator garden would be complete without its showiest inhabitants: the butterflies. We’ve got a wealth of host plants for butterflies in the Old Forest, which is full of native trees whose leaves caterpillars love to eat. But our summertime nectar sources at Overton Park can be sparse, with just a few wildflowers able to thrive under the dense tree canopy. So a sunny spot bursting with flowers must be a welcome sight for the butterflies. None of these four lay eggs on anything that’s planted in this location, so they’re strictly here for the nectar.

It’s wonderful to see butterflies patronizing your nectar bar, but the ultimate victory in a garden like this is when they start laying eggs and creating the next generations. With that in mind, we went all in on encouraging black swallowtails by planting both parsley and fennel. Anecdotally, I’d only ever seen one black swallowtail in Overton Park, a stray flying through the forest last spring. But thanks to the garden, the population has exploded. We’ve had several different cycles of egg-laying and tiny caterpillars that gradually grow substantial until they look like cheerful Slinkies working their way up a stem. Most caterpillars move away from their host plants when they’re ready to begin their metamorphosis, but one swallowtail set up shop underneath the lip of the flower bed, right above a park bench. I checked the chrysalis every day, hoping to see the butterfly emerge, but sadly the magic happened without me. Perhaps the large group of caterpillars that appeared this week will afford me another chance!

The fennel was a roaring success, but what about the milkweed? I’m happy to report that one morning I saw a monarch laying eggs on all three species we’d planted, and the following week we saw close to a dozen caterpillars scattered throughout (probably from an earlier round of egg-laying). They’ve gone off somewhere to pupate, but I’m hopeful that we’ll see a new generation of adults emerge soon. That generation will fly south toward Mexico, another link in the chain of a population that needs milkweed throughout the country to survive its long migratory journey.

My daily visits to the garden have been one of the absolute highlights of my summer–visiting with the bugs that show up every day and searching amongst the flowers for unexpected visitors. I hope that if you haven’t had the chance to stop by this special place, you’ll head over while the plants are still in bloom. Once they begin dying back, I look forward to the next phase: watching what kinds of finches and other birds come to eat the seeds!