NatureZen: Biophilia and Park Design

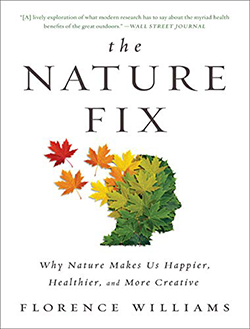

Overton Park Conservancy is thrilled to welcome journalist and author Florence Williams to town for a special evening at the Brooks Museum on Wednesday, October 19. Ms. Williams’ influential 2017 book The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative explores research that shows how time spent in nature strengthens our relationships, improves our health, and promotes reflection and creativity. Her new book Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey dives into how the experience of awe–often in a natural setting–can help us heal after traumatic experiences.

Overton Park Conservancy is thrilled to welcome journalist and author Florence Williams to town for a special evening at the Brooks Museum on Wednesday, October 19. Ms. Williams’ influential 2017 book The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative explores research that shows how time spent in nature strengthens our relationships, improves our health, and promotes reflection and creativity. Her new book Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey dives into how the experience of awe–often in a natural setting–can help us heal after traumatic experiences.

We hope you’ll join us to hear the science behind why nature is such a healing force. Tickets are $25 per person and include a reception, talk, and book signing. Reserve your space today!

Our Executive Director, Tina Sullivan, has been deeply inspired by Florence Williams’ work and her call to reconnect strongly with nature. As we’ve worked on the comprehensive plan for Overton Park over the past few years, she has kept the theme of biophilia in mind, and today she shares some of her inspiration with you.

NatureZen: Biophilia and Park Design

by Tina Sullivan

When George Kessler began designing Overton Park in 1901, he believed he should let the natural beauty of the place speak for itself and uplift the souls of those who visited. He said the Old Forest, with its wild landscape, was the park’s most important feature, and must be preserved.

Kessler was a contemporary of Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the designers of Central Park in New York. They were both part of the City Beautiful Movement, which pursued beautiful design as a tool to uplift citizens and instill in them a sense of civic pride. Within this context, I wanted to learn more about how nature inspires design, and how we might maximize our natural assets not only to make Overton Park more beautiful, but to use this place to uplift our city.

The definition of biophilia, according to Harvard entomologist E. O. Wilson, is “residing in the natural world, identifying the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms, as an evolutionary adaptation aiding not only survival but broader human fulfillment.” In other words: we need nature. If you, like me and many others, turned to gardening and cultivation of houseplants as solace and comfort during the pandemic, you were experiencing biophilia. It’s why you walk into the Old Forest at Overton Park and immediately let out a sigh of relief.

Florence Williams, in her book The Nature Fix, presents an array of research results pointing toward what should be intuitive – that humans exposed to nature show reduced cortisol levels and blood pressure, along with higher alpha brain waves described as a relaxed attentiveness that leads to creative problem-solving, stronger immune systems, and general feelings of happiness and well-being.

Williams acknowledges that these ideas aren’t new. She points out that Frederick Law Olmsted wrote in 1865 that viewing nature “employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.”

Our bodies and brains long to connect to the natural world, and thrive best when that connection is reinforced. We are basically highly evolved primates who have a predictable physiological need to connect with the natural world around us. And yet we find ourselves increasingly divorced from the natural environment. But we can mitigate that disconnect with an intentional return to nature, preferably literally and directly, through forest bathing or even a well-placed window or some houseplants. And we can be intentional about designing our environments to be mindful of our biological compulsion toward the natural world, which is as easy to predict as the sunflower’s compulsion to follow the sun.