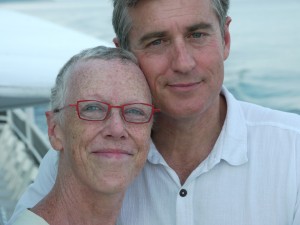

Stories: Bill Stegall

Bill Stegall has spent more important times in his life in Overton Park than he can count. Here he recalls coming of age in the park with the backdrop of civil rights and the antiwar movement, and falling in love with his beautiful wife Margaret, who passed away last year.

My relationship with the park started when I was about ten or eleven years old, when my parents finally gave me the liberty to have a bicycle and disappear for hours at a time. It attracted me because I would be sitting at Snowden—I was a Greenie—and I would hear the lions roar. In those days there was no air conditioning, so the windows were always open. At 2:00, which happened to be my algebra class, I would hear the lions roar—it was time to be fed. At ten or eleven, I had the opportunity to get on my bicycle and sneak away to the park, which was a vast territory to explore.

And then when I was 14, I read Walden by Henry Thoreau. It was the first serious book I ever read, and I was just swept away by it. And one of the things that interested me was how well Thoreau knew Walden Pond. He knew everything about it. He says in the book that if he were asleep and you dropped him down and woke him up at some time of the year, he could tell within a couple of days what day on the calendar it was by looking at how many lichen were on the trees or where the birds were. And so I decided, well, if Thoreau can learn Walden Pond, then I was going to learn Overton Park.

I took it very seriously. I got out maps, and I drew the park and traced all of the footpaths. At one time I had a complete detailed map of Overton Park—all the footpaths and where things were. So if someone says, “You know where the big clay pots are that are broken?” I know exactly where that is. I knew where there was a hawthorn tree that was one of the largest hawthorns in America. The big trees, I called the grandfathers—I knew where they were and when they died. I mourned at their passing. My passion all the way through school was Overton Park.

I became more serious about it when I saw social developments happening that were reflected in what was happening at the park. For example, for a while the park was kind of the center for the antiwar movement. On Sundays everybody who had hair down below their collar would meet at the park and smoke very weak marijuana and talk about ending the war. It’s just where the alternative culture had a place to go.

One time the police were clearing us out of the park. I was about 14 and I was very interested in that world. My father was a union organizer so I got to go and see the marches downtown—the only 14-year-old white boy to march with Dr. King! So I was very interested in the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement. The police came one time and tried to clear us out of the park. We all got in the water and started splashing the police and said, “Come and get us!” It was just hysterical. They didn’t know what to do—were they going to take their shoes off and roll up their pants legs and come wading in after us, or were they going to be macho and just jump in? Either way they couldn’t catch us! They finally jumped in the water after us, so we just ran off into the woods. So all the cultural things that were happening outside the park were going on inside the park as well.

And of course, I fell in love with my wife at the park. That’s the greatest story I have to tell. Years later as an adult, in my mid-20s, I took Margaret to the park. And she took me over to this honeysuckle vine. She took off one of the mature honeysuckle flowers. She pulled the stem and put the honeysuckle off my lips and kissed it off. That was it. I was hooked. And we were married for 30 years. Anytime we were living in Memphis, that’s where we were. It was our place.

Want to share your own story of Overton Park? Join us at the Memphis & Shelby County Room on the 4th floor of the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library on Saturday, June 29 (1:00 – 4:00pm). Details here.